Beechwood

Images

Organs

This is what started it.

In the mid-1960s I had become interested in the electronic production of music. Our physics teacher had a selection of pamphlets published by the

British valve manufacturer Mullard Ltd. Each pamphlet described a small electronic constructional project utilising the relatively novel transistor, by now

also manufactured by the Mullard company. (Inconsequentially but slightly interestingly the transistor and I were born at the same time – January 1948)

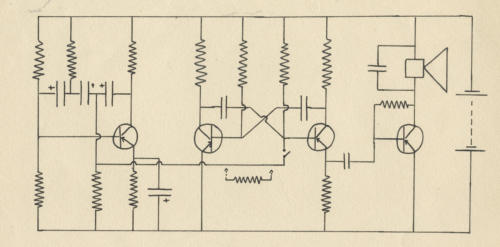

One of these pamphlets described an electronic organ using germanium transistors (OC71) and consisted of a multivibrator as a tone source which was

modulated by a phase-shift oscillator. The tone source was tuned by a series of resistors selected by the keyboard switches. My father, who worked as a

laboratory technician at a technical college in Cardiff, managed to scrounge some bits and it was he that constructed the organ on a piece of simple

matrix board. He knew little of electronics and laid the circuit out much as it appeared in the diagram but he was an excellent solderer and the result

was a work of art - I wish I still had it.

Furthermore, it worked well; a one-octave keyboard was fashioned from clothes pegs (my father’s idea, the physics teacher was amazed) and strips of

balsa wood; I had an electronic organ. It was fairly basic, the audio was an untreated square wave, there was an intrusive click when a key was pressed

and tuning was very tricky but, it was a start.

It was around this time that I found a book in my excellent local library. It was titled “The Electronic Musical Instrument Manual” and was written by Alan

Douglas. This book, I am half-ashamed to say is before me now and I can see that it was first borrowed from the library on 5th April 1963 – probably by

me. This book was on loan to me almost permanently until the new edition appeared. A comprehensive manual, it describes the theory and practice of

generating organ sounds with lots of examples of circuit techniques - nearly all valves at this time of publication;1962 – and details of large pipe-

emulating instruments, portable monophonic keyboards as well as my introduction to the mighty Hammond. I was hooked.

The portable monophonic instruments were of great interest to me; a large twin keyboard polyphonic instrument was possible for the home

constructor and designs were available but the cost and effort was impossible for an O-Level schoolboy, while the simpler, short keyboard, “one-note-at-

a-time organ was a possibility and this style of organ was popular with several “beat-groups” at the time; remember The Tornadoes “Telstar”? This tune

was -probably- played on a Jennings (later, Vox) Univox which sold for just under £100 back in the early 1960’s - (about £2,500 today) - the circuit details

of which were described in detail in Alan Douglas’ book. Thus, my simple device formed the basis of a more sophisticated instrument; two octaves of

keys were taken from an old pub piano, elastic bands were used as springs and phosphor-bronze strips as key contacts, further, two frequency dividers

were added with some basic tone-forming to give a quite repectable little instrument. I recall I fashioned, from scratch, some sliding switches - a la

Hammond - to select various tones. It was all mounted in a hardboard case, with an amplifier, speaker and a hinged lid.

Later, I think in 1968 the hobbyists magazine “Practical Electronics” published

constructional details for a transistorised, two-manual polyphonic organ

designed by the aforementioned Alan Douglas. I was, by now a card carrying

member of the Electronic Organ Constructors Society (I still am) and I

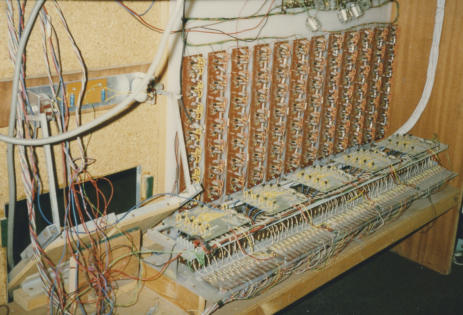

undertook construction of this project. Here are some photographs.

Twelve Hartley oscillators, each feeding a chain of seven frequency dividers

generated the tones. A 60x4 diode matrix did the keying via a clever anti-bump

circuit (anITT application note) which I incorporated. Active low-pass filtering, in

octave sections provided flue tones. Phew, are you still with me?

I completed the ”Great” - lower manual section and it worked well but with

limitations, for instance there were no non-octave sounds, very limiting for a good

instrument. The “Swell” - upper manual was all planned out but never materialised.

Technology had overtaken my efforts, integrated circuits were now the norm - even

“organ-on-a-chip” was available. So, the project petered out. It would have needed

a complete rebuild, almost from scratch to get what I wanted and I was now

playing guitar in a good band and did not have the time. No regrets, the project

absorbed me for many years and was very rewarding. A little later I bought a

Hammond T200 with a Leslie speaker which I loved but sadly gave away when I left

London.

I do have a Hammond organ today, it looks like this:

A computer modeled Hammond B3 with Leslie; It sounds great and does not spill oil on the carpet.

© Lorem ipsum dolor sit Nulla in mollit pariatur in, est ut dolor

eu eiusmod lorem 2013

SIMPLICITY